Catfish-Duck Ponds for the Mississippi Delta

Catfish farmers, waterfowl biologists, and duck hunters have known since the 1970s that catfish ponds in the Mississippi Delta attract tens of thousands of ducks and other waterbirds annually. Mississippi State University (MSU) wildlife scientists conducted aerial surveys of ducks throughout the Delta, including surveys of catfish ponds during winters 2002 through 2004. They found more than 105,000 acres of catfish ponds in the Delta attracted an average of more than 110,000 ducks in winter. That’s more than a duck per acre of catfish pond. And nearly 30 percent of all ducks in the Delta were observed on catfish ponds. These data indicate significant duck habitat exists on Mississippi catfish ponds.

Because catfish ponds provide permanent wetlands for waterfowl and other water birds, species that prefer such habitat occur most often on these ponds. Primary species include northern shoveler (spoonbill), lesser scaup (bluebill), ruddy duck, coots, and cormorants. Less abundant waterfowl include gadwall (gray duck), mal- lard, teals, canvasback, ringnecked duck, and Canada geese.

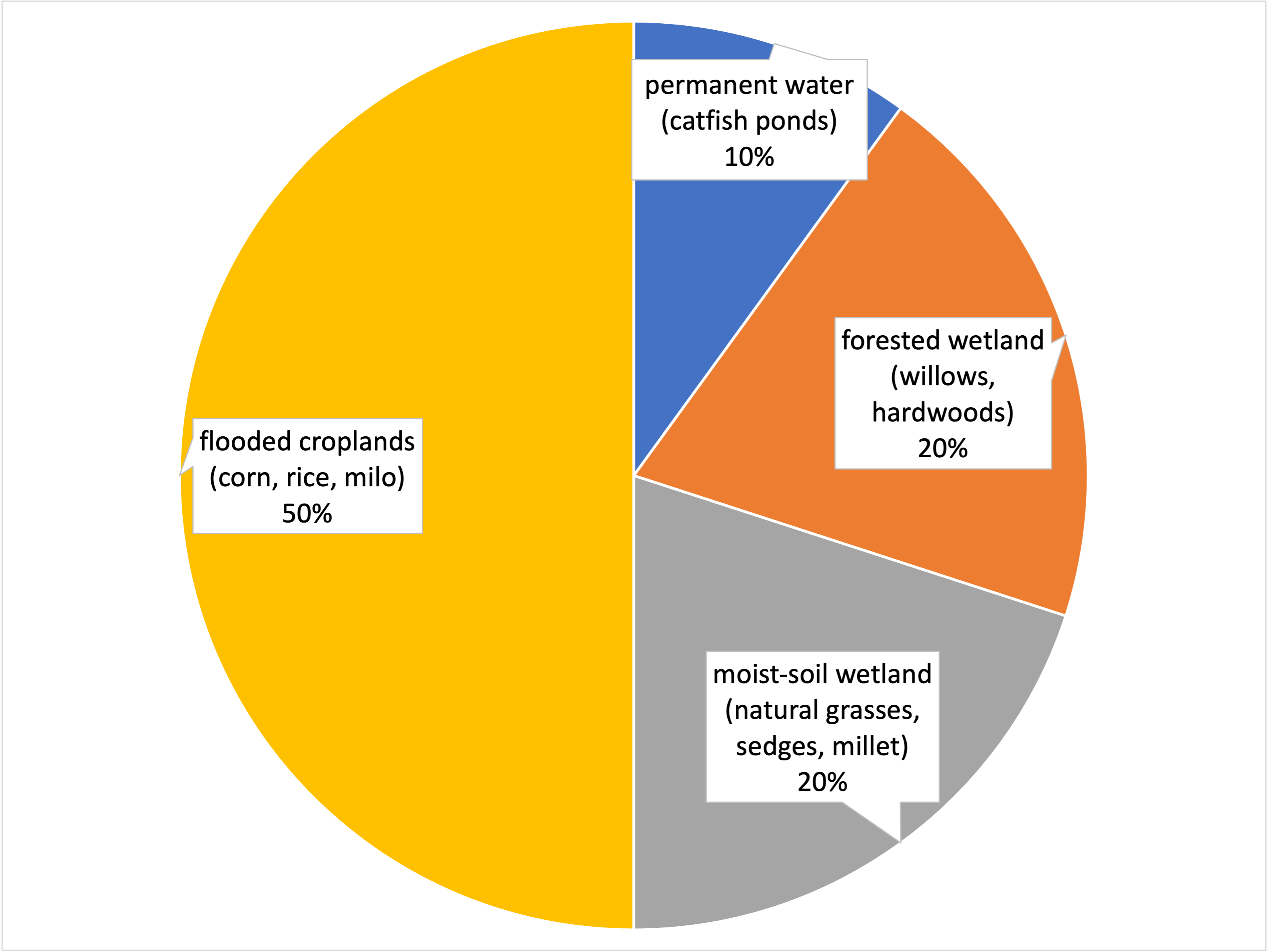

All these duck and goose species can be attracted to catfish ponds if producers elect to retire some ponds from fish production and create a waterfowl “habitat complex.” The MSU wildlife scientists recently discovered the greatest winter-time abundance of mallards and other dabbling ducks across the Delta was associated with habitat complexes containing about 50 percent flooded cropland, 20 percent forested or scrub-shrub wetlands, 10 to 20 percent “moist-soil” wetlands with natural grasses and sedges, and the remainder permanent water as in catfish ponds.

The MSU wildlife scientists recommend that catfish producers interested in creating waterfowl habitat include these habitat types among nearby ponds selected for waterfowl management. The exact percentages may not be as important as managing for a habitat complex containing flooded crops, woody vegetation, moist- soil vegetation, and permanent water (such as catfish ponds). For example, if 10 or so catfish ponds were retired from fish production, four or five ponds could be planted to cereal crops (such as corn, milo, and rice).

Willows could be encouraged to grow in a couple of the ponds in patches or along inside pond edges but not on the levees, because tree roots weaken levees over time. Natural moist-soil grasses and sedges or seeded millets (such as Japanese, browntop, or Chiwapa) could be encouraged to grow along with cereal crops or in separately managed ponds or areas of ponds. Catfish ponds remaining in production would provide the permanent wetland. Lastly, if possible, the duck “habitat complex” should be located inside the fish pond complex, away from highway traffic and other frequent disturbances.

Such a complex of duck habitats provides the birds with high-energy cereal grains, natural seeds, and aquatic invertebrates for energy and protein, cover for waterfowl and hunters, and open-water areas for diving ducks and during winter freezing periods. Duck-managed ponds probably will not be attractive to cormorants if kept shallowly flooded (6 to 18 inches) and vegetated during winter.

If you’re not managing all your ponds for catfish production, consider managing some for waterfowl and waterfowl hunting. Waterfowl hunters are seeking wetlands to lease. Your ponds may provide a valuable added source of income for the family and farm (see Legal Considerations for Leasing Catfish-Duck Ponds).

Wonder Weeds for Waterfowl*

*Excerpts from this section were originally printed in the Spring 2007 issue of Delta Wildlife magazine.

As the name implies, “moist-soil” plants are adapted for living and reproducing in wetlands. They thrive in seasonally flooded wetlands, which are not flooded year-round but remain “moist” during the growing season. Waterfowl managers consider moist-soil plants “wonder weeds” for ducks and geese. Here’s why.

Moist-soil plants generally are annuals that produce abundant seeds and tubers each year because of their short life spans. Abundant production of seeds and tubers is good news for waterfowl because ducks, geese, and swans worldwide feed on these natural morsels of energy and other important nutrients.

In the delta of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, where wetlands and agriculture abound, migrating and wintering waterfowl feed heavily on natural and agricultural seeds such as rice. But MSU wildlife scientists discovered the abundance of waste rice—grain missed during harvest—and other crop seeds have decreased significantly over the past 25 years.

Although grain harvest machinery has become more efficient in recent years, the decrease is largely because earlier harvests leave seeds in the field to decompose or get eaten by blackbirds, snow geese, and rodents. The seeds sometimes sprout but generally do not have enough time to produce a mature plant and seed head in the fall before frost and wintering waterfowl arrive.

Moist-soil seeds and tubers can fill part of the “grain gap” caused by decreased abundance of waste crop seeds. Harvested rice fields in late fall contained only about 70 pounds of waste rice per acre compared to almost 500 pounds of moist-soil seeds per acre in managed wetlands.

Moist-soil seeds and tubers can make up for the decreased abundance of waste crop seeds, and many of the plant species targeted in moist-soil management provide nearly as much seed and tuber energy for waterfowl as agricultural seeds. For example, MSU scientists have reported that mallard ducks can obtain, on average, about 3.2 kilocalories of energy by eating a gram of corn, rice, or soybean compared to about 2.8 kilocalories from a gram of moist-soil seeds such as from barnyard, foxtail, and panic grasses.

Clearly, moist-soil plants seem to be “wonder weeds” for waterfowl. So how do we grow them? A good summary of moist-soil plant management is covered in Extension Publication 1864, “Waterfowl Habitat Management Handbook.” Briefly, to produce moist-soil plant communities, managers should disk soil in spring or early summer and then try to keep soils moist, but not flooded, during the growing season.

Disking soil every year or two and keeping it moist during the growing season promotes germination of the natural “seed bank” and stimulates vigorous and diverse plant growth. But don’t disk in the heat of summer (late July through August). Soil disturbance during the “dog days” of summer generally promotes germination of weeds such as coffeeweed, cocklebur, and sicklepod.

If undesired weeds appear, herbicide applications may be needed to prevent weeds from overtaking the moist-soil plants. Again, Extension Publication 1864 identifies a variety of herbicides useful in controlling unwanted weeds. Always remember to use herbicides that kill broadleaf weeds and vines but do not harm desired moist-soil grasses and sedges (2, 4-D).

What about growing moist-soil plants with “hot” foods such as rice, corn, and milo? Actually, rice, corn, and milo compete well with moist-soil grasses and provide greater food energy for waterfowl than most natural seeds. The MSU scientists are studying what they term “dirty rice” and “grassy corn and milo.” Basically, moist-soil grasses and sedges are allowed to grow amongst grain crops that are not harvested but left for wintering ducks.

“Grassy corn,” in particular, can increase potential duck use per acre about tenfold, because corn yields more bushels of seed and has a greater energy value than moist-soil seeds. Corn grown with moist-soil grasses produces an abundance of high-energy corn and a diversity of natural plant and animal foods for wintering waterfowl. Grassy corn is planted at low seed densities and in rows about 3 feet apart.

To produce grassy corn, habitat managers plant corn at a reduced seed density, such as about 16,000 seeds/acre, and apply herbicide once, either before or soon after planting, to let the corn grow about a foot tall and establish a good root system without weed competition. The widely spaced rows and decreased seeding rate let sunlight reach grasses and sedges that will grow amid the corn plants. Fertilizer and irrigation also may be necessary for pro- duction of normal cobs.

After grassy cornfields are flooded 6 to 18 inches deep in fall-winter, they provide corn and abundant moist-soil seeds and aquatic invertebrates, which are critical sources of protein for ducks. The flooded grass under the corn is critical habitat for invertebrates. Indeed, the combination of high-energy corn, the stalks providing cover for waterfowl, and the protein-rich invertebrates—all within “swimming space” for waterfowl—make flooded “grassy corn” a “duck magnet,” especially for mallards and other dabbling ducks.

Legal Considerations for Leasing Catfish-Duck Ponds

Landowners can readily lease these impoundments and associated properties to hunters to earn supplemental income on their lands. First, owners need to determine if leasing ponds for waterfowling or wildlife watching will interfere with existing farming practices and whether they want hunters and visitors on their properties. If the answer is yes, landowners next need to examine ways to reduce potential accident liability concerns from hunters and visitors’ paying to recreate on the property. As a paid invitee, owners owe visitors additional assurances that the property will be made reasonably safe for recreation as required by Mississippi law. The following list of recommendations should be considered to reduce potential hazards on the property and to protect yourself from legal actions resulting from hunting or recreational accidents that might occur on your property.

- Eliminate hazards on the property that might cause accidents to occur. For example, remove single-strand cable gates, inspect and repair blinds, repair or remove damaged bridges on the property, and inform invitees of livestock and horses on the property.

- Advise invitees in writing of any known hazards on the property, and have each individual sign an acknowledgment of such and a hold-harmless waiver of any liability from accidents occurring on your land.

- Have well-written leases in place that have been reviewed by an attorney with hunting clubs leasing your property.

- Establish property-use rules, and enforce them to the letter.

- Acquire liability insurance. Be careful to review policy exclusions and require hunting clubs or individuals leasing your property to obtain insurance coverage specifically naming you as an insured party.

- Contact your attorney to consider establishing a limited liability corporation (LLC) as a holding company of your land leased for hunting or as part of an outfitting enterprise. Through this arrangement, your outfitting business leases the property from your LLC to conduct your hunting or leasing operation. In the unlikely event that an individual is injured while on your property and wins a legal lawsuit against your hunting operation, your most valuable asset, your land, will be protected, since it is held under the LLC.

For additional information on reducing potential liability from leasing your land or operating a fee-access outdoor recreational business, go to the Natural Resource Enterprises Program website.

|

Activity |

Period |

|---|---|

|

Drain pond. |

March–June |

|

Disk soil* and plant corn, milo, rice, and/or millet; or drill seeds into substrate. Apply herbicide only at time of planting to promote growth of natural grasses with cereal crops. |

April–June |

|

Spot spray noxious weeds (coffee weeds) with herbicides that will not kill grasses and cereal crops (such as 2,4-D**). |

June–September |

|

Flood to create mud flats to 6 inches of wetland depth for teal, shorebird, and wading bird habitat. |

August–September |

|

Gradually flood duck habitats 6–18 inches deep. |

October–December |

*Take soil sample to ensure salt concentration will not prevent germination and survival of plantings.

**Verify that the timing of herbicide applications does not violate county spray restrictions during early cotton season.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products or trade names are made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended against other products that may also be suitable.

Publication 2482 (07-23)

By Bronson K. Strickland, PhD, Extension Professor, Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture; Richard M. Kaminski, PhD, Professor, Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture; Aaron T. Pearse, PhD, Wildlife Research Biologist, USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND; and W. Daryl Jones, PhD, Assistant Extension Professor, Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.