Mississippi Vegetable Gardener's Guide

Grow Your Own Vegetables

Growing a vegetable garden in Mississippi can be highly rewarding. Gardeners can enjoy the freshest produce ripened in their own garden. Sometimes only minutes elapse between harvest, preparation, and consumption. Even if you don’t consume the food on the day of harvest, it typically lasts longer in storage than store-bought produce. That’s because most fresh vegetables at the grocery store travel about 1,800 miles between producer and consumer, and it often takes several days to be received. Additionally, gardeners have more variety available to them and are not limited to what is stocked at the stores.

Vegetable gardens have a long history in Mississippi. In the past, a family’s food often came right from their own garden. Today, gardening is typically much more recreational. Regardless of the motives, gardeners want a successful harvest from what they plant. This resourceful guide aims to provide key information to successful gardening.

What to Plant

While Mississippi’s climate is not suitable for all fruits and vegetables, we can grow a tremendous assortment because of our long growing season. But while you can grow many types of produce, there’s no sense in planting something your family won’t eat.

Once you decide what to plant, consider how much to plant. This decision is based in part on the days required

for a plant to reach maturity (when it can be harvested) and how much of each vegetable your family can eat. Another important factor is how much garden space you have. Some vegetables take a lot of garden space and a long time before they can be harvested, while others are planted and harvested in a short time, producing abundantly in a small space.

Most melons, pumpkins, vining types of squash, and sweet potatoes take several months to mature and take up a considerable amount of garden space. Typically, they are harvested over a short time, but the produce has a long shelf life. Most okra, tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, and pole beans also grow for several months in the garden, but they typically can be harvested continuously. Sweet corn takes a considerable amount of garden space, but many gardeners feel it is worth it to be able to enjoy the incredible sweetness of freshly harvested corn that typically cannot be matched by corn purchased at the grocery store.

For gardens with limited space, consider planting smaller vegetables: bush, snap, and lima beans; leafy greens like lettuce, spinach, mustard, collards, Swiss chard, and turnips; green onions; tomatoes; sweet peppers; and eggplant. As space permits, add broccoli, cabbage, hot peppers, okra, summer squash, southern peas, and pole beans. Watermelons and pumpkins take up much more space. Cucumbers, which normally take up a lot of ground space, can be trellised. For gardeners who only have a patio available, a growing number of vegetables have been developed for containers, such as the Patio Snacker cucumber and the Micro Tom tomato. They are very small but produce abundantly for their size.

Irish and sweet potatoes are productive for the garden space required but can be difficult to store long term. For example, long-term storage of sweet potatoes is best at 55 to 60 degrees.

Choose varieties recommended for growing in hot, humid climates. Look for varieties that are labeled with “good” or “excellent” disease resistance to multiple diseases. Many new varieties offer much better disease resistance, higher yields, and great flavor. The varieties you choose can make a big difference in how successful you will be. For example, there are tomato varieties available today that are highly resistant to multiple diseases, yield over 20 pounds of tomatoes per plant, and have exceptional, competition-winning flavor. Keep a gardening journal to keep track of what you liked, what worked, and what didn’t.

Vegetables grown for their fruits or seeds, such as sweet corn, tomatoes, squash, cucumbers, eggplant, peppers, beans, and peas, should be planted in the sunniest spots. Vegetables grown for their leaves or roots, such as beets, cabbage, lettuce, mustard, Swiss chard, spinach, and turnips, can grow in partial shade, though they perform better in direct sunlight.

Succession Planting

Many people who grow gardens only plant once during the spring. But in Mississippi, we have the opportunity to grow and harvest produce almost year-round. The long growing season combined with successive plantings (growing more than one vegetable in the same space during the year) optimizes what the garden can produce.

As soon as one vegetable is harvested, space can be cleared, prepped, and planted with another. For example, follow an early-spring planting of English peas with a late-spring planting of cucumbers; then replant the space with fall bush snap beans, leafy greens, or late southern peas. Another example is to follow early sweet corn with winter squash and pumpkins in early July. Spring Irish potatoes can be followed by lima beans or southern peas, which are followed by fall greens.

Practice crop rotation (planting nonrelated plants in the same location in successive plantings) to prevent disease buildup in the garden soil. Rotation should be by family groups. For example, don’t replace tomatoes with peppers since they are in the same family.

When growing vegetables (like snap beans, sweet corn, lettuce, radishes, leafy greens, and southern peas) that are intended to be consumed fresh from the plant, make small successive plantings of vegetables.

Planting at 2-week intervals provides continuous fresh vegetables. Plant only as much as your family can eat before the next planting begins to produce. If you plan to can and freeze as well as use fresh vegetables, plant more vegetables at one time to provide enough at harvest for preserving.

Table 3 (page 16) lists expected yields for the different vegetables. Keep in mind that the estimated yields given for some vegetables (tomatoes, peppers, okra, pole beans, and eggplant, for example) are for multiple harvests over a period. Vegetables with extended harvest periods require only one planting during the season. However, with tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant, a second planting made in midsummer provides good-quality vegetables for a fall harvest.

A second planting of okra, about 6 weeks after the first planting, has some benefit for late-season harvest, but you can get the same benefit by cutting the first planting back to a height of 3 to 4 feet in late summer.

Plant your garden according to a detailed plan. A finished garden plan shows the following:

- vegetable varieties

- number of successive plantings for each vegetable

(if applicable) - planting dates and locations

- row spacing

Related Vegetable Groups

Tomato, Eggplant, Irish potato, Pepper

Cucumber, Squash, Pumpkin, Muskmelon, Watermelon

Snap bean, Lima bean, Peanut, Southern pea

Cabbage, Broccoli, Turnip, Mustard, Collard

Garden Location

The ideal garden site is close to the house but out in the open where it receives full sun and is not shaded by trees or buildings. Choose a place that is near a water supply and has loose, fertile, well-drained soil.

Few gardeners are fortunate enough to have the ideal garden site or soil. This does not mean growing a successful garden is impossible. If you select the right vegetables and carefully manage the soil, some vegetables can be produced in almost any location.

Select a site free of serious weed problems. Nutsedge, torpedograss, bermudagrass, cocklebur, and morning glory are just a few of the weeds that are difficult to control in a garden.

Fence the garden site to keep out children and animals. A two-strand, low-voltage electric fence may be the only way to keep small animals like rabbits and raccoons out. Remove low tree limbs that hang over the garden and give animals access.

Garden Layout

Design your garden to meet your needs. Careful planning reduces work and can make the garden more productive. Randomly planting seeds and plants will likely result in waste and disappointment.

Consider your available equipment when designing the shape of your garden. Where the work is done with a tractor, long rows are practical. Therefore, a long, narrow, rectangular garden would be more practical than a more square-shaped garden. When cultivation is by hand, the shape is much more flexible, but be sure to mound the soil for each row to improve drainage.

Also, consider the slope of the land; run rows perpendicular to the slope, especially on sandy-textured soils that tend to wash and erode. Where the land is uneven, contour the rows.

Rows for small vegetable plants, such as carrots, onions, and radishes, can be laid closer together for hand cultivation than for power equipment. Planting them in double rows or a broad band in a row can increase the yield from a small garden plot.

Closely spaced rows and vegetable plants help shade out weeds and reduce water loss from the soil surface. However, this also reduces air movement and increases chances for diseases. Be sure to leave enough space between the rows to work around the plants comfortably but keep rows close enough together to get more produce from a smaller area. Cover the rows with mulch, such as pine straw, leaves, grass clippings, shredded paper, or newspaper, to prevent weeds from germinating and reduce soil erosion.

Plant perennial vegetables, like asparagus, where they won’t interfere with yearly land preparation. Plant long-season vegetables, like tomatoes, okra, peppers, and eggplant, together where they won’t interfere with short-term vegetables and replanting. Plant corn, okra, pole beans, staked tomatoes, and other tall vegetables on the north side of the garden so they won’t shade or interfere with the growth of shorter vegetables.

To get fuller ears from sweet corn, plant them in a block of at least four rows rather than one or two long rows. This will help to ensure good pollination. When possible, group vegetables according to their lime and fertilizer needs. Southern peas, lima beans, snap beans, and peanuts do not require as much nitrogen fertilizer as other vegetables.

Soils

Garden Soil

The ideal garden soil is deep, loose, fertile, and well-drained (internally as well as on the surface); has plenty of organic matter; and is free of weeds and diseases. Such soils can sometimes be difficult to find, but less-than-ideal soils can be just as productive with proper preparation and management.

Water moves quickly through well-drained soil and never completely shuts off air movement. Drainage is important because roots cannot develop, live, or function without a constant oxygen supply. Clay soils dry slowly after rain because their pores are small, and water moves through them slowly. Sandy soils, on the other hand, have many spaces and dry out quickly.

Clay and sandy soils can be successfully remedied by adding organic matter. Increasing the organic matter in clay soil improves the tilth, makes it easier to work, and improves its drainage. Adding organic matter to sandy soil increases its water-holding capacity and improves its fertility.

Garden soil affects the way vegetable plants grow and look. When soils are cold, wet, crusty, or cloddy, seedlings are slow to emerge, and some may not survive. Root rot diseases may take a heavy toll on seedlings, especially beans. Other soil-related plant symptoms are stunted plants, slow growth, poor color, and shallow, malformed roots. Signs of poor soil structure are crusts, hard soil layers below the surface known as hardpans or fragipans, standing water, and erosion.

Increase the soil’s organic matter content by adding manure, composted leaves, sawdust, bark, or peat moss. Also turn under plant residues like sweet corn stalks and green manure crops (soybeans, rye, southern pea plants, and others) after harvest. Plant residues should be free of diseases if they are to be added to the garden soil. Cover crops, such as clovers and vetch, planted in the fall prevent soil erosion and leaching of plant nutrients. They also provide organic matter and nitrogen when turned under in spring.

Manures vary in nutrient levels, and the amount of straw, age, exposure to weather, and degree of composting changes their composition. Be careful not to overfertilize when applying chicken litter to garden soil. Use no more than 200 pounds per 1,000 square feet of garden space. Cow and horse manure is lower in nutrient content than poultry manure and can be applied at 250 to 300 pounds per 1,000 square feet. It is best to use manure that has been aged (composted) for at least 3 months to avoid nitrogen depletion from composting it in the garden. This can use too much nitrogen in the soil and cause plants to suffer.

Overuse of manures can add so much fertilizer to the soil that plant growth is harmed. Most organic materials release some nutrients quickly and the rest over time. (See the Organic Gardening section on page 42 for more information.) While adding organic matter improves soil fertility, manures and plant residues are not balanced fertilizers, and soils require additional fertilizer. Test the soil every year or two and make adjustments as recommended.

Soil Preparation

Plants and seeds are easier to establish and grow better in well-prepared soil. The initial prep work is typically best started in the fall, except in areas where erosion could be a problem. Consider using an approved herbicide to kill existing weeds or turfgrass before working the soil for new garden plots. Apply lime, if needed, at the rate recommended from your soil test. Break the soil with a plow, rototiller, or spade. Plow or turn the soil to a depth of 7 to 8 inches. (Many smaller garden tillers will struggle or fail at this task.) Leave fall-plowed land rough until spring.

In early spring, you can disc or rake the soil several times at regular intervals to keep down weeds, break up clods, and smooth the soil.

If you did not plow or spade the garden site in the fall, turn the soil in spring as soon as it is dry enough to work. For most soils, you’ll know it is dry enough when you can shape a handful of soil into a ball that crumbles when you press on it with your thumb. Soil that is too wet will be sticky, and the ball will stay intact. Avoid working wet soils.

Just before planting, apply fertilizer (and lime if it was not added in the fall or earlier in the spring) as recommended. Then, pulverize the soil with a rototiller (or harrow) to get a smooth, level surface. This helps to firm the soil, break up clods, and leave a smooth surface for seeding. Soil left in rough condition for several days after turning in the spring may dry out and form hard clods, making it much more difficult to prepare a good seedbed. Especially where the soil is clay, level, and likely to stay wet, use a hoe, rake, or rototiller to pull the soil into raised rows that are 10 to 12 inches across on the tops. Let the sides slope gently to the walkways to provide good surface drainage.

Conventional row spacing is 36 to 40 inches apart, but spacing depends on the farming equipment, garden size, and vegetables being grown. Rows for large, vining vegetables like watermelons, cantaloupes, pumpkins, and winter squash are usually 6 to 8 feet apart.

Raised Beds

Raised beds can help where gardening space is limited or the soil quality is poor. For example, if the site is low and collects water or the soil drains poorly, using raised beds will avoid these problems. Raised beds are planting areas where the soil is several inches higher than that of the natural grade. This is accomplished by adding soil to the growing area or incorporating soil amendments, such as compost, sand, composted sawdust, or bark, into the existing soil.

In areas where the soil is extremely poor, you can excavate and replace it with a homemade custom soil blend, a commercial soil blend, a soilless potting mix, or topsoil. Before going to this extreme, it is recommended that you first get the soil tested and amend the existing soil as directed. A soil test could potentially save you a significant amount of time, labor, and money. (See the Soil Testing section on page 6 for more information.)

Where the native soil is adequate, you can make raised beds by pulling the soil from the walkways and placing it on the beds. Then, fill the walkways with mulch materials like pine straw.

Raised beds can be framed with wood, bricks, or concrete blocks, or they can be left unframed. The framing adds to the appearance and keeps the soil in place. Depending on the materials used and the design, it may even provide seating.

Ideally, raised beds should be no wider than 4 feet (so you can easily reach the center from either side) and no longer than 25 feet unless crossovers are provided. Beds 4 feet wide and 25 feet long contain 100 square feet and make calculations for rates of fertilizer easier. Beds accessible from only one side should be narrower than 4 feet so you can reach across the whole bed from one side. All framed beds should be of the same width so that covering materials (shade frames or sashes for cold frames) fit all beds, making crop rotation easy.

Raised-bed soil that has been improved by adding organic matter and sand often enables excellent root crops like carrots, onions, turnips, and parsnips to grow, even though they would not grow in the native soil. Select vegetables that produce a lot for the space they occupy. Trellis vining crops like cucumbers, pole beans, Malabar spinach, and melons. Support melon fruit in slings. Raised beds require more water than ground-level beds, but when the alternative is no garden at all, it’s worth the extra effort.

Here are some additional advantages of raised-bed gardening:

- Raised beds produce more vegetables per unit of garden space because space is not wasted with walkways between every row.

- Soil in raised beds dries and warms more quickly in spring, which permits earlier planting and harvest of spring vegetables.

- Soil does not become compacted because you don’t walk on it.

- Closely spaced plants in raised beds shade out weeds and reduce the need for frequent cultivation.

Raised-bed gardening, however, does have some disadvantages:

- It can be difficult to space plants properly. Plants without adequate space will take over other plants’ space.

- Closer plant spacing can reduce airflow and increase disease problems.

- Raised beds require more frequent watering because of improved drainage.

- Raised beds may require more frequent fertilization because of the leaching that results from frequent watering and improved drainage.

- Raised beds may not be compatible with equipment.

- Raised beds are more expensive to create.

Container Gardening

Container gardening is available to anybody who has sunlight and a source of water. Appropriate containers for growing vegetables have a low center of gravity, keep the growing medium from washing away, and allow water to drain from the bottom. Quart-sized (or larger) pots and cans can grow herbs, radishes, lettuce, strawberries, and other small plants. Tomatoes, peppers, squash, eggplant, and other large plants need a container that will hold 5 gallons or more. Old ice chests, bathtubs, barrels, and other large containers can support several plants, but don’t forget to add drainage holes.

Fill containers with disease-, insect-, and weed-free soilless potting mix. Do not use garden soil in containers. You can make your own blend with compost, peat moss, or other organic material and sand. Sand helps with drainage and provides weight for stability. Organic or synthetic fertilizers supply needed nutrients. Water is the most limiting factor in container gardening because plant roots are restricted. Container gardens often need to be watered twice on hot summer days.

Composting

Compost is organic material that is broken down by microorganisms into simpler organic and inorganic compounds. Soil mixed with compost has improved soil structure, tilth, fertility, and water- and nutrient-holding capacity. Compost can be mixed directly into the garden soil or used as mulch on the soil surface. If you choose the second option, work the compost into the soil after harvest or at the end of the season.

The most significant benefit from compost is its value as a soil conditioner. Compost increases the water-holding capacity of the soil, reducing the frequency that you need to water. Adding compost improves both sandy and clay soils. Plant nutrients in compost include nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. They are mostly in an organic form, and they release slowly and are less subject to leaching.

Compost is something you can make at home, but composted bark and manure can also be purchased. Make compost from vegetable scraps from the kitchen and other plant materials from normal yard chores, such as leaves and grass clippings, or hauled-in materials like sawdust, straw, or hay. Remember to use only vegetative materials and no meat, chicken, or fat scraps.

Construct a pile by alternating layers of plant waste material and soil. Keep the pile moist and add a mixed fertilizer to speed the composting process. Alternate layers of fresh, nitrogen-rich materials (including fresh grass clippings, vegetable scraps, and coffee grounds) and dry, carbon-rich materials (including hay, dry leaves, straw, and sawdust) in a volume ratio of approximately 1:3.

Make sure the straw or hay came from a field that was not treated with pyridine carboxylic acid-based herbicides, such as aminopyralid, clopyralid, and picloram, since these compounds may not be broken down during the composting process and can severely damage your vegetables.

Locate your compost pile out of sight. It can be built on open ground or in a bin made of cinder blocks, rough boards, old pallets, or wire fences. The sides of the bin should not be air- or water-tight. Spread a layer of the organic matter about 6 inches deep and, if desired, add 1 cup of a mixed fertilizer like 6-8-8 to every 10 square feet of the surface. Then add 1 inch of soil and enough water to moisten but not soak the pile. Repeat this process until the pile is 4 to 5 feet high. Make the top of the pile concave to catch rainwater. Under normal conditions, turn the pile in 2 or 3 weeks and again in 5 weeks.

The heat generated from the materials breaking down helps decomposition. Moist, green plant materials and fresh manure decompose much faster than dry, brown materials and can produce a considerable amount of heat. If you start the compost pile in the fall, decomposition will be slow until spring and summer. See Extension Publication 1782 Composting for the Mississippi Gardener for more information.

Soil Testing

The soil reaction, or measure of acidity or alkalinity, is based on a scale of 1 to 14 and is referred to as pH. A pH of 7.0 is neutral. Any values below 7.0 are acidic, and any values above 7.0 are basic or alkaline.

The ideal pH value for garden soil is between 6.0 and 7.0. Vegetables do not grow well in acidic soils with a pH of 4.5 to 5.5 or in alkaline soils with a pH above 7.5. To determine your soil pH, you will need to get it tested. Contact your county Extension office for a soil test box and instructions for taking a soil sample. There is a $10 fee for complete analysis (pH plus nutrient analysis with lime and fertilizer recommendations) on each sample. The limestone (lime) recommendation is the most important piece of information on a soil test report.

In areas with high rainfall like Mississippi (average of 55 to 60 inches per year), soils are generally acidic. However, there are exceptions, particularly in the Delta and Blackland Prairie, and the pH can easily fall outside of the optimal range for vegetable gardening. Of all soil samples analyzed at Mississippi State University’s Soil Testing Laboratory from 2015 to 2020, 51 percent had a pH of 5.9 or below and needed lime. Only 31 percent of soil samples had a pH between 6.0 and 7.0.

The soil test tells you if and how much lime is needed. Lime is the most effective and inexpensive aid available for soil improvement. The soil’s calcium and magnesium levels tell you what form of lime to apply—dolomitic (magnesium and calcium) or calcitic (calcium). An acidic soil that tested medium-low to very low in magnesium should be limed with dolomitic (high-magnesium) lime. An acidic soil high in magnesium can be limed with either calcitic limestone or dolomitic limestone.

Plants growing in highly acidic (or highly basic) soils will grow slowly, partly because of poor root growth. This makes them more susceptible to drought stress and less efficient at absorbing soil nutrients, and they may develop symptoms of nutrient deficiencies.

Ideally, you should apply lime to acidic soils well ahead of planting (2 to 3 months) to provide time for it to dissolve and change the soil pH. However, lime begins to react as soon as it is incorporated into the soil and can be applied at any time to increase soil pH levels. The best time to apply lime is in the fall.

Apply lime evenly over the entire area and work it into the top 4 or 5 inches of soil. Incomplete mixing may make future tests show a need for more lime, which can result in applying too much lime and poor plant growth. Lime not only raises the soil pH but improves soil fertility. Lime also improves the structure of clay soils and makes them easier to work.

Adding lime to the soil is not a once-in-a-lifetime event. Since soils limed to the proper pH return to their acidic state with time, test the soil every year or two to determine if additional lime is needed. Sandy soils become acidic again faster than clay soils.

These are some factors that cause soil pH to drop:

- using acid-forming fertilizers

- lime leaching from the soil with rain and irrigation water

- organic matter decomposing and releasing organic acids

Soil test results are reliable only if you take samples properly:

- Use a spade or trowel to remove a slice of soil 6 inches deep.

- Get similar sections from other random places in your garden.

- Put these samples in a pail or box.

- Mix the soil thoroughly.

- Remove about 1 pint of the well-mixed soil and dry it at room temperature.

- Place the dried soil in a soil test box or other container.

Do not take samples where fertilizer has been spilled or manure has been piled. Also, do not include debris such as leaves, sticks, roots, or large stones in your sample. Deliver the soil sample to your county Extension office.

Fertilizer Needs

The amount of fertilizer to apply depends on the soil’s natural fertility, amount of organic matter, type of fertilizer, and vegetables being grown. Get a soil test to determine your garden’s fertilizer needs.

In addition to soil testing, you also must measure your garden to determine the number of square feet it occupies. Garden fertilizer recommendations are based on 1,000 square feet, and an area of 1,000 square feet could measure 25 by 40, 20 by 50, 30 by 33, or other dimensions according to your plot layout.

If your area is smaller than 1,000 square feet, divide the actual area by 1,000, then multiply the decimal figure by the recommended lime and fertilizer rates. For example, if your plot measures 16 by 24, the area contains 384 square feet; 384 divided by 1,000 equals 0.384; multiply 0. by your recommended fertilizer rate to determine the amount of fertilizer to apply.

Vegetable plants require many different nutrients for good growth and production, but the three major nutrients that usually require the most attention by gardeners are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) are also very important, but they are supplied by limestone. All other nutrients are obtained from air, water, and soil.

Mixed fertilizers are normally sold by grade (signified by their “N-P-K” numbers) and contain two or three major plant nutrients. The N-P-K refers to the percent nitrogen (N), available phosphate (P2O5), and available potash (K2O).

Fertilizer sources of the major plant nutrients are ammonium sulfate (21 percent nitrogen, 21-0-0), a blend of ammonium sulfate and urea (34 percent nitrogen, 34-0-0), nitrate of soda (16 percent N, 16-0-0), calcium nitrate (15.5 percent N, 15.5-0-0, plus 19 percent Ca), urea (46 percent N), superphosphate (46 percent P2O5, 0-46-0), and muriate of potash (60 percent K2O, 0-0-60). Phosphorus and potassium do not easily leach from garden soils like nitrogen; therefore, they can build up to very high levels in regularly fertilized gardens. In these cases, nitrogen is the only fertilizer recommended since additional phosphorus and potassium are unnecessary.

Where nitrogen is the only fertilizer recommended, the usual recommendation is 3 pounds of 34-0-0 (3 pints) per 1,000 square feet of garden space before planting. Measuring the amount of fertilizer to apply is important because adding too much can damage plants and adjacent water sources. It can even leach into the underground water supply.

Vegetables differ in their fertilizer requirements. Leafy greens like mustard, turnips, collards, cabbage, and spinach are heavy users of nitrogen. Broccoli and sweet corn also require more nitrogen than some other vegetables. While nitrogen is important to the plant growth of fruit and root vegetables, phosphorus and potassium are important to the proper development of roots and seeds. Peanuts, southern peas, and beans get nitrogen from the air and do not require heavy nitrogen fertilization. Overfertilizing these vegetables with nitrogen causes excessive growth of leaves at the expense of the fruit.

Apply fertilizer before or at planting. Two methods of application are “in the row” and “broadcast.” For most gardeners, the broadcast method is more practical.

To broadcast, spread the recommended amount of fertilizer evenly over the soil surface and then thoroughly mix it into the soil while preparing the beds. Heavy-feeding vegetables need additional fertilizer (side-dressing) after the plants are well established (see Table 1).

For row application, apply the recommended fertilizer to the row. Mix it thoroughly with the soil so that it will not damage the seed and tender plants.

Fertilizer can be applied in a combination of broadcast and row applications. Broadcast two-thirds of the recommended fertilizer over the entire garden surface and mix it into the soil. Apply the remaining one-third of the fertilizer in furrows 3 inches to the side of the row and slightly below the level of the seeds.

Nitrogen fertilizer applied before or at planting time usually does not supply all the nitrogen needed during the growing season for heavy- and medium-feeding vegetables. Also, irrigation and rain can leach water-soluble nutrients, especially nitrogen, into deeper areas of the soil, out of the reach of the roots of shallow-rooted vegetables.

Apply (side-dress) additional nitrogen fertilizer along the row, 4 to 6 inches from the base of established plants, being careful to keep all fertilizer off plant leaves.

Table 1. Side-dress applications of nitrogen*.

| Crop | Timing |

|---|---|

| beans | At three- to four-leaf stage. |

| beets, carrots | 4–6 weeks after planting. |

| bell peppers, eggplant, tomatoes | After first fruit set and again at 4- to 6-week intervals. |

| broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts | 3 weeks after transplanting or after danger of late freeze in spring; broccoli again when heads begin to show. |

| cucumbers, muskmelons, watermelons, winter squash | When vines begin to run. |

| English peas | When plants are 4–6 inches tall. |

| Irish potatoes | When sprouts break through soil surface. |

| leafy greens (mustard, turnips, chard, collards) | When plants are about one-third grown. |

| lettuce, kohlrabi, Chinese cabbage | 2 weeks after transplanting; 4 weeks after sowing seed. |

| okra | After first pods are harvested. |

| onions (green and bulb) | From sets: when tops are 6 inches high. From transplants: when established and actively growing. |

| peanuts | None |

| radishes | None |

| southern peas | None |

| summer squash | Before bloom when plants are 8–10 inches tall and again in 4 weeks. |

| sweet corn | When 8 inches high and again when knee high. |

| sweet potatoes | None |

| turnips (roots), rutabagas | 4 weeks after sowing seeds. |

| tomatoes | When first fruit are 1 inch in diameter and again at first harvest. |

*1 pint of 34-0-0 per 100 feet of row, 3⅓ tablespoons per 10 feet of row.

Planting

Planting Dates

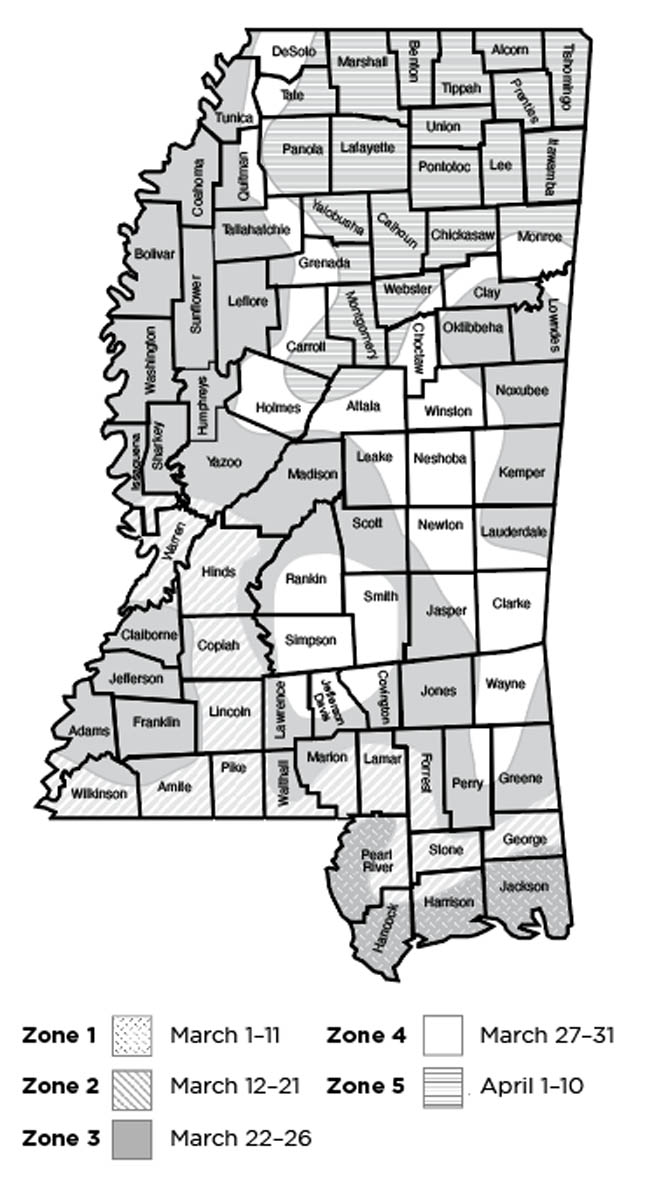

Use Figure 1 and Table 2 to determine planting dates for vegetables in your garden. Identify your garden’s zone (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5) using the map. Some Mississippi counties are divided into two or more zones.

The zones are based on weather data for the median (most frequent) dates of last freezes (temperature of 32°F or less) in spring. Freezes can occur before or after the median dates listed for each zone, but this is rare. Each vegetable has been categorized as cool- or warm-season, and the recommended planting dates make up the body of information in the table.

Beets, for example, are recommended for planting in zone 1 from February 1 to March 1. The starting dates are 4 and 6 weeks before the last median frost date for the zone for cool-season vegetables, and 2 and 4 weeks after the last median frost date for warm-season vegetables. The cut-off date for planting cool-season vegetables is to provide sufficient time for the vegetables to mature before the heat of summer. The cut-off date for planting warm-season vegetables is to permit maturity and harvest before disease, insect, and weather pressures become too great and before cold temperatures in the fall.

Most cool-season vegetables can be planted in both spring and fall, allowing gardeners to harvest in both seasons. Crops like broccoli, cabbage, Chinese cabbage, cauliflower, collards, kale, spinach, Swiss chard, and rutabagas are higher quality and produce over a longer period when planted in the fall. Most warm-season vegetables can be planted over a period of several weeks ranging from midspring to midsummer.

Table 2. Spring and summer planting dates.

Cool-Season Vegetables

| Vegetable | Zone 1 | Zone 2 | Zone 3 | Zone 4 | Zone 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beets | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Mar. 1 | Mar. 15 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 5 | |

| broccoli (plants) | Feb.1 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Feb. 15 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 10 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 20 | |

| cabbage, collards (plants) | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Feb. 15 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 20 | Apr. 1 | |

| carrots | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | |

| cauliflower (plants) | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Feb. 15 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 10 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 20 | |

| chard, Swiss | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Mar. 1 | Mar. 15 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 5 | |

| kohlrabi | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Mar. 1 | Mar. 15 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 5 | |

| lettuce, head | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Mar. 1 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 5 | Mar. 10 | |

| lettuce, leaf | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 10 | Apr. 15 | |

| mustard | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 20 | |

| onions (sets or plants) | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Mar. 1 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 15 | |

| peas, English | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Mar. 10 | Mar. 10 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 20 | Apr. 1 | |

| potatoes, Irish | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb. 13 | Feb. 18 |

| Feb. 15 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 10 | Mar. 15 | |

| radishes | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb.22 | Feb.27 | Mar. 3 |

| Mar. 15 | Mar. 15 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 15 | Apr.25 | |

| spinach | Jan. 20 | Jan. 29 | Feb. 8 | Feb.13 | Feb.18 |

| Feb. 15 | Mar. 1 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 15 | Mar. 15 | |

| turnips | Feb. 1 | Feb. 12 | Feb. 22 | Feb. 27 | Mar. 3 |

| Apr. 1 | Apr. 1 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 20 |

Warm-Season Vegetables

| Vegetable | Zone 1 | Zone 2 | Zone 3 | Zone 4 | Zone 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beans, snap bush | Mar. 15 | Mar. 25 | Apr. 4 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 14 |

| Apr. 15 | Apr. 20 | May 1 | May 1 | May 10 | |

| beans, snap pole | Mar. 15 | Mar. 25 | Apr. 4 | Apr. 9 | Apr. 14 |

| Sept. 1 | Aug. 15 | Aug. 15 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 1 | |

| beans, lima bush | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Aug. 15 | Aug. 1 | Aug. 1 | July 25 | July 15 | |

| beans, lima pole | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Aug. 5 | Jul. 20 | Jul. 20 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 5 | |

| corn | Mar. 1 | Mar. 11 | Mar. 21 | Mar. 26 | Mar. 31 |

| Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | |

| cucumbers | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Sept. 14 | Aug. 28 | Aug. 21 | Aug. 14 | Aug. 10 | |

| eggplant (plants) | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Aug. 15 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 1 | July 15 | |

| muskmelons | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | May 15 | Jun. 1 |

| May 1 | May 1 | May 15 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 | |

| okra | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | Jul. 15 | |

| peanuts | Mar. 15 | Mar. 25 | Apr. 4 | Apr. 9 | Apr. 14 |

| May 1 | May 1 | May 1 | May 15 | May 15 | |

| peas, southern | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Aug. 10 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 1 | Aug. 1 | Jul. 20 | |

| peppers (plants) | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Aug. 15 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 1 | Jul. 15 | |

| potatoes, sweet (plants) | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | |

| pumpkins, winter squash | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | Jul. 1 | |

| spinach, New Zealand | Mar. 15 | Mar. 25 | Apr. 4 | Apr. 9 | Apr. 14 |

| Apr. 15 | Apr. 15 | Apr. 20 | May 15 | May 15 | |

| squash, summer | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Sept. 14 | Aug. 28 | Aug. 21 | Aug. 14 | Aug. 10 | |

| tomatoes (plants) | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| Aug. 15 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 10 | Aug. 1 | Jul. 20 | |

| watermelons | Mar. 29 | Apr. 8 | Apr. 18 | Apr. 23 | Apr. 28 |

| May 1 | May 1 | May 15 | May 15 | Jun. 1 |

Compare New Varieties to Established Varieties

Every year, companies release new varieties that are advertised as having superior yield, taste, and disease resistance. Such claims are often true, but advertised claims may not hold true in your own garden. You can conduct a side-by-side comparison by planting a new variety next to your go-to variety. You may be surprised to find that your go-to variety has been outmatched.

In addition to making your own comparisons, universities conduct trials regularly throughout the country on new varieties, and their results are usually made available online. It is important to note that trials done in the southeastern U.S. are likely to be more reliable for Mississippi gardeners than trials conducted in other parts of the country.

Transplants versus Seeds

Small plants (called transplants or starts) or seeds of vegetables are available in many local and online stores. Transplants can give certain vegetables a head start on the growing season and help avoid diseases that can develop later in the season.

Planting transplants of warm-season vegetables like tomatoes, tomatillos, peppers, and eggplant is standard practice and recommended over direct-sowing these crops. Grafted versions of these transplants are available and are increasing in popularity, offering enhanced disease resistance and higher yields.

Cool-season transplants of cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, head lettuce, and onions are also recommended. While you can purchase transplants of cucumbers, squash, cantaloupes, and watermelons, the extra time needed to become established after they are transplanted is often longer than directly sowing seeds into the garden, so you may want to direct-seed these crops.

Some vegetables like sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, and garlic are grown almost exclusively from vegetative parts (slips, cut-up tubers, or separates cloves, respectively) rather than from true seeds. The nursery industry uses the term “seed” for Irish potatoes even though they are not real seeds. “Seed potato” refers to actual potatoes that need to be cut into pieces before they are planted.

You can purchase or grow your own vegetable transplants in a cold frame, in a hotbed, in a greenhouse, on a light bench, on a sunny porch, or by a sunny window. See Extension Publication 3436 Homegrown Flower, Herb, and Vegetable Transplants for more details.

There are many advantages of growing your own plants:

- They are substantially less expensive.

- They are available when you need them.

- You can grow the specific varieties you want.

- You reduce the chances of introducing new diseases and insects into your garden.

You can successfully grow transplants of many vegetables by following a few simple guidelines:

Seed

Transplants require several weeks to grow, so get your seeds early. Start them at the appropriate time so they will be large enough to handle for transplanting but not so large that they outgrow their containers and become unwieldy to manage. Store unused seeds in an airtight container in the refrigerator, where they may last for many years.

You can test the viability of old seeds by placing 10 or so seeds between two moistened paper towels in an airtight container or plastic bag. Store it in a warm, dark place. Check the bag every couple of days to see if the seeds begin to germinate. Toss packets of seeds that fail to germinate. Alternatively, fresh seeds can be purchased every year to avoid germination problems.

Soil

Do not use garden soil because it does not provide proper drainage and can be contaminated with disease and weed seeds. Several commercial sterile, soilless seed starting mixes are available, or you can prepare your own:

- 2 quarts sphagnum peat moss (remove any large sticks)

- 1 quart vermiculite

- 1 quart perlite

- 1 tablespoon limestone

Container

Containers for seed germination can be plastic or Styrofoam egg cartons, half-pint milk cartons, small trays, aluminum foil loaf pans, pie tins, peat pots, or peat pellets. Dry, soilless media repels water, so lightly moisten it before filling containers. Make sure larger containers have drainage holes before filling them nearly to the top with the soilless mix. Small containers like egg cartons do not require drainage holes if they are watered carefully.

Expandable peat pellets (available at nurseries and garden supply stores) eliminate the need for a mix. Place dry, flat pellets in a shallow tray and sprinkle them several times with warm water until they are completely expanded. Allow a little time between sprinklings. Surround the expanded pellets with sand or vermiculite to hold them upright and slow their drying between watering.

Planting Seeds

Do not plant too many seeds; a little goes a long way. Plant them at the depth recommended on the back of the seed packet. Generally, larger seeds are planted deeper than smaller seeds. When using trays or pans, plant the seeds in rows and cover with ¼ inch of the potting mix or vermiculite. Vermiculite is a great medium to cover the seeds since it has a contrasting color from the seed starting mix and helps keep seeds moist. When using individual containers, plant two or three seeds per container. With the expanded pellets, make a small depression in the top and drop in one or two seeds.

Transplants are recommended for triploid, or seedless, watermelons. To aid germination, plant seedless watermelon seeds with the rounded end facing down and the pointed end facing up.

Germination

Cover containers with a germination dome or a piece of plastic or slip them into a clear plastic bag to keep the humidity high. The best temperature for germination is 75 to 80°F. Lower temperatures will slow down germination. Tomato, pepper, and eggplant seeds won’t germinate at temperatures below 60°F. Even at the optimum temperature, eggplant and pepper seeds may take 2 weeks to germinate. If you’re using an egg carton, keep the lid on until the seeds begin to germinate. Make sure the soil stays moist but is not overly saturated, as this may cause the seeds to rot.

Seeds do not require light to germinate. But as soon as the seedlings begin to emerge from the mix, remove the cover, lower the temperature, and increase the amount of light to prevent spindly growth. Place cool, white (4000K+), 40-watt fluorescent or LED tube lights several inches above the seedlings. Provide 18 hours of supplemental light per day. An outlet timer may be helpful. If the weather is warm during the day, you can set the trays outside, but be sure the soil stays moist. Bring trays inside during cool or cold nights.

Tomato, pepper, and eggplant seedlings grow best when the day temperature is 70 to 75°F and the night temperature is 60 to 65°F. Broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower prefer cooler temperatures—65 to 70°F during the day and 55 to 60°F at night. At these temperatures, broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower take 5 to 7 weeks to reach an appropriate size for transplanting to the garden. Peppers and eggplant may need 8 to 10 weeks. Seedless watermelon requires about 3 weeks.

Thinning and Transplanting

Individual containers with more than one seedling must be thinned to one plant. Pinch out or cut off the extra seedlings while the first leaves are still small.

Seedlings germinated in trays must be transplanted to individual containers while still small. Lift and separate seedlings and replant them into individual containers such as peat pots, plastic cell-packs (saved from previously purchased transplants; be sure to wash them), peat pellets, or other small containers. Use a commercial soilless potting mix or prepare your own.

Fertilizer

Commercial seed-starting mixes may contain enough fertilizer to grow the seedlings. These are referred to as “charged.” Check the packaging for details. Homemade mixes of peat, vermiculite, and perlite contain no fertilizer; fertilize seedlings for optimal growth starting just as the first true leaves start to develop from the cotyledons.

An all-purpose, liquid-soluble fertilizer (such as 20-20-20) can be mixed at a rate of 50 to 75 ppm nitrogen. Fertilizer packaging often has a table listing the amount of fertilizer required to reach the target ppm concentration per gallon of water. Fertilize one to three times per week. Be sure not to overfertilize as this can damage tender seedlings.

Store excess fertilizer solution in a dark, cool place in an airtight container to prevent evaporation. Use it as the plants grow.

As the plants develop more true leaves, fertilizer rates can be increased to 75 to 150 ppm. It is important to supply an appropriate amount of fertilizer. Plants suffer from both insufficient and excessive amounts of fertilizer. Too little fertilizer is better than too much because more fertilizer can be added later if needed.

Disease

Damping-off is the major disease that attacks seedlings, especially when the medium is kept excessively wet. Seedlings suffering from damping-off appear pinched at the soil line, fall over, and die. See the Vegetable Diseases section on page 28 for more information.

Hardening Off

Transplants grown in a cold frame are stockier and better able to withstand outside garden conditions than transplants grown indoors or in a greenhouse. Before setting out tender transplants, place them in a cold frame for 1 to 2 weeks to acclimate them to colder temperatures, brighter light, and wind. This greatly increases their chances of survival once set in the garden.

If a cold frame is not available, move plants outdoors for an increasing amount of time during the day over the course of 1 to 2 weeks to harden them off. Bring them back inside if nights will be cool. Not doing so often causes excess stress on the transplants and slows down their establishment in the garden.

Cold Frame

Cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower transplants are easy to grow in an outside cold frame. Build a simple frame and cover it with polyethylene. Plants grown in a cold frame require 8 to 10 weeks to reach the size for setting in the garden, so start early. Place the cold frame in a sunny location with the low side facing south and the high back facing north. Paint the inside white to reflect light and promote uniform growth.

Since temperatures in a cold frame are frequently below the optimum for seed germination, plant seeds in a soilless mix in trays and germinate them indoors. Once the seeds have germinated, move the trays to the cold frame. Open or remove the cold frame cover for ventilation on clear days when the air temperature is 45°F or higher. Thin the seedlings to stand ½ inch or more apart. Crowding results in spindly, weak transplants. Fertilize to promote growth.

Growing onion transplants requires considerable time. Start by planting seeds in September or October in closely spaced rows in a cold frame. Transplants will be ready for setting out in January and February. To have transplants of cabbage, broccoli, and other cool-season vegetables ready in time for spring planting, you must start very early in the year, which may not be practical. Transplants of these vegetables can be grown for the fall garden.

Sweet potato transplants (slips) are produced by planting sweet potatoes in beds of sawdust or sand. Maintain the temperature in the bed close to 80°F. Since disease problems can be carried on the mother roots and transmitted to the slips, it is better for gardeners to purchase their sweet potato slips or to use vine cuttings. Vine cuttings are made by cutting potato slips above the surface of the bedding material. The cuttings develop roots rapidly when planted in warm, moist garden soil.

Buying Transplants

When buying vegetable transplants, select recommended varieties. Plants with good roots that are healthy (white, not brown or black), stocky, medium-sized, and free of diseases or insects are best. Avoid yellow, spindly, or oversized plants and those with spotted foliage, brown marks on the stems, or knots on the roots.

Transplanting to the Garden

At an appropriate planting time, dig a hole in the prepared soil. Being careful not to damage the stems, remove the transplants from their plastic pots. Place your hand over the top of the pot with the stem between your index and middle fingers, and invert the plant into your hand. Then, carefully loosen the root ball and place it into the hole.

Do not remove transplants grown in fiber pots, such as peat pots, before planting. Cover fiber pots completely with soil, making sure not to leave the upper edges exposed to the air. Plant tall tomato transplants deeply so that the lowest set of leaves is close to the soil surface.

Starter Solution

Plants cannot grow properly without all the necessary nutrients. Garden centers often sell fertilizer that is specially formulated with higher phosphorus content to help roots establish quickly in the garden, but most soils in Mississippi have adequate phosphorus for proper and healthy root growth. Check your soil test results to see if this is the case in your garden. The limiting nutrient in Mississippi soils is often nitrogen; therefore, plants typically establish faster with supplemental nitrogen, not phosphorus, at the time of transplant.

Protection

Depending on the weather, it may be necessary to protect newly set plants from sun, cold, and wind. Homemade shelters include boxes, baskets, flowerpots, and plastic milk containers. Commercial hot caps of paper or plastic and devices containing water protect young, tender plants from frost. A wooden shingle stuck in the ground at a slant on the south side of a plant serves as a sunshade. A piece of newspaper or a paper grocery bag pinned down over a plant provides protection from the sun.

Wrap the bottom 12 to 18 inches of wire tomato cages with clear plastic to provide some protection to transplants from wind, cold, and blowing sand. You may prefer to avoid this hassle altogether by planting the garden a week or two later when the weather is warmer. Also, warm-season vegetables do not grow well in cold soil and cool air temperatures. Therefore, planting extra early—before the weather warms in the spring—may not be that beneficial in terms of earlier and larger yields.

Planting and Thinning Tips

Start with fresh seeds or older, properly stored seeds with good germination. You can plant older seeds, but use more seeds to make up for their lower germination rates. Begin by marking straight rows with stakes and a string or cord. Add fertilizer if you did not already do so.

Rake the seedbed clean of clods, rocks, and other debris. Make shallow furrows suitable for small seeds by drawing a hoe handle along a string. For deeper furrows, use a corner of the hoe blade. In the spring, plant seeds shallowly to speed germination. As the season progresses, plant seeds deeper to ensure a good supply of moisture.

Small seeds are difficult to distribute thinly and evenly and are easier to space if mixed with dry sand or dry, pulverized soil before planting. When planting small seeds like carrots that germinate slowly, mix in some radish seeds to mark the row. The radishes will germinate very quickly.

Seeds that are large enough to handle easily can be planted in groups (hills) or spaced evenly (drilled) in the row. Either way is acceptable. When planting in hills, place several seeds in small areas at the desired final plant spacing. Sweet corn, squash, pumpkins, watermelons, cantaloupes, and okra are often planted in this way.

Space seeds of beans, peas, beets, chard, and sweet corn evenly down the row. Space individual seeds 1 or more inches apart but at a spacing closer than the desired final plant spacing.

After the seeds are placed, cover them with soil. (See Table 3 on page 16 for the recommended depth of planting). Carefully firm (do not pack) soil over the seeds with the flat blade of a hoe. Be careful not to plant seeds too deeply. Seeds covered with too much soil do not germinate.

Once the seeds germinate and the seedlings are established, remove the excess seedlings. Thin sweet corn, okra, and summer squash to one plant per hill, pumpkins and melons to two plants per hill.

Thinning seems wasteful, especially to new gardeners, but it prevents crowding. Leaving the plants spaced too closely together reduces yields, makes the plants more susceptible to disease, and generally starves the plants for water and nutrients because of the excess competition.

In the thinning process, try to save the strongest seedlings and remove excess plants with a hoe, rake, or your fingers. Where seedlings are very close together and pulling disturbs the roots of the remaining plants, pinch out or cut the excess plants. If carefully removed during thinning, seedlings of some vegetables can be transplanted and used to fill in empty places or shared with other gardeners. Excess lettuce and other greens can be eaten.

The temperature of the garden soil at planting affects how quickly seeds germinate or if they germinate at all. Most cool-season vegetable seeds germinate at a soil temperature of 60°F, while most warm-season vegetable seeds germinate slowly at a soil temperature of 75°F. The longer seeds are in the soil without germinating, the more they are subject to attack by diseases and insects. Black plastic mulch is an effective way to raise the soil temperature to allow early planting of warm-season vegetables. (For more information, see the Mulching section on page 17.)

Other materials available to home gardeners are plastic row tunnels and floating row covers that allow early planting and provide some protection from cold. You can use plastic tunnels in combination with black plastic mulch. Floating row covers made of non-woven polyester also provide early insect protection.

Pollination

Pollination is the transfer of pollen within a flower or between flowers. For leafy (greens, spinach, cabbage) and root (beets, carrots, radishes) vegetables, pollination is not important since you are not harvesting fruit. But for vegetables we grow for their developing fruit, ripened fruit, or seeds (melons, corn, tomatoes, squash, pumpkins, okra, etc.), pollination is almost always needed.

Pollen is produced in the anthers (male parts) and must be moved to the pistil (female part). One part of the pistil, the ovary, develops into the seed or fruit that is eaten—squash, tomatoes, cucumbers, and corn kernels. Pollen is transferred from the anthers to the pistil in one of three ways: wind, insects or birds, and self-pollination.

Corn pollen is carried by the wind as it falls from the tassel to the silks of the ears. Corn planted in a single row has a much lower pollination rate than corn planted in a block of adjacent rows. High temperatures and drought do not interfere with pollination (the transfer of pollen) but can prevent proper fertilization, resulting in poorly developed ears.

The pollination process in all beans, peas, and tomatoes is called self-pollination because the transfer of pollen takes place within the individual flowers without the aid of insects or wind.

Squash, pumpkins, melons, gourds, and most cucumbers are insect-pollinated. In these vegetables, which have the male and female flower parts in separate flowers (yet still on the same plant), insects transfer pollen from male flowers to female flowers while going from flower to flower, collecting nectar and pollen.

Bees often are seen on vegetables that are wind- and self-pollinated, where they are collecting pollen and nectar. Since pollinating insects are so important in the garden, it is important to consider them when choosing and applying insecticides. Choose insecticides that are least toxic to bees and apply them late in the day when bees are not actively working in the garden.

Vegetables that are self- and insect-pollinated can suffer from lack of pollination and fertilization, just as wind-pollinated corn does. High temperatures, shade, and insufficient moisture often result in pollen that is unable to properly pollinate the pistil. Incomplete pollination results in poorly shaped fruit (cucumbers, watermelons, tomatoes).

Except for corn, cross-pollination between different vegetables is an unnecessary concern to gardeners. All summer squash, pumpkins, vegetable spaghetti, acorn squash, and small ornamental gourds are closely related and will cross if planted close to one another. Jumbo pumpkins and most winter squash can cross. If you grow several varieties of summer and winter squash and pumpkins in the same garden, purchase fresh seed each year.

Different corn colors (yellow and white) and types (standard sugary, sugary enhanced, supersweet, field, and pop) cross-pollinate if planted close to one another if they silk and tassel at the same time. Results can vary from a few yellow kernels on normally all-white ears to a situation where the corn is not fit to eat. All sweet corn must be isolated from the field corn and popcorn, and all supersweet corn must be isolated from all other corn. To prevent cross-pollination in corn, isolate different types at 250 feet apart, or stagger the planting dates so the maturity dates between the corn types are at least 14 days apart. This also applies to cross-pollination with field corn.

Table 3. Planting guide.

| Vegetable | Seeds or plants per 100 feet | Depth of planting (inches) | Distance between plants (inches) | Average crop expected per 100 feet | Average days to harvest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asparagus | 1 oz | 1 | 18 | 30 lb | 2 years |

| 65 plants | 6–8 | ||||

| beans, snap bush | ½ lb | 1 | 3–6 | 60 lb | 50–55 |

| beans, snap pole | ½ lb | 1 | 4–12 | 80 lb | 65 |

| beans, lima bush | ½ lb | 1 | 3–6 | 47 lb in shell | 65 |

| 18 lb shelled | |||||

| beans, lima pole | ½ lb | 1 | 4–12 | 66 lb in shell | 80 |

| 25 lb shelled | |||||

| beets | 1 oz | ½ | 2 | 75 lb | 65 |

| broccoli | ⅛ oz | ¼–½ | 18–24 | 50 lb | 80–115 |

| 50–65 plants | 18–24 | 50 lb | 75 | ||

| cabbage | ⅛ oz | ¼–½ | 12–18 | 150 lb | 100 |

| 65–100 plants | 12–18 | 150 lb | 80 | ||

| cabbage, Chinese | ⅛ oz | ¼–½ | 12 | 100 lb | 80 |

| carrots | ⅛ oz | ¼–½ | 2 | 100 lb | 75 |

| cauliflower | ⅛ oz | ¼–½ | 18–24 | 80 lb | 80–115 |

| 50–65 plants | 18–24 | 80 lb | 65 | ||

| chard, Swiss | 1 oz | ¼–½ | 6 | 75 lb | 50 |

| collards and kale | ¼ oz | ¼–½ | 8–16 | 150 lb | 55 |

| corn, sweet | 3–4 oz | 1–2 | 12 | 10 doz | 80 |

| cucumbers | ½ oz | 1 | 12–18 | 100 lb | 55 |

| eggplant | 50 plants | 24 | 150 lb | 85 | |

| kohlrabi | ⅛ oz | ¼–½ | 3–4 | 75 lb | 55 |

| lettuce, head | ¼ oz | ¼ | 12 | 75 head | 80–115 |

| 75–100 plants | 12–14 | 75 head | 80 | ||

| lettuce, leaf | ¼ oz | ¼ | 8–12 | 50 lb | 50 |

| muskmelons | ¼ oz | 1 | 36–48 | 100 fruit | 90 |

| mustard | ¼ oz | ¼–½ | 2 | 100 lb | 45 |

| okra | 1 oz | 1 | 12–18 | 90 lb | 65 |

| onions, green | 600 sets or plants | 2 | 100 bunches | 35 | |

| onions, bulb | 220 sets or plants | 6 | 100 lb | 110 | |

| parsley | ⅛ oz | ¼ | 4–6 | 30 lb | 90 |

| peanuts | ½ lb | 1–2 | 3–4 | 45 lb green | 110 |

| 15 lb dry | |||||

| peas, English | 1 lb | 1–2 | 2 | 30 lb in shell | 65 |

| peas, southern | ½ lb | 1 | 4–6 | 40 lb in hull | 65 |

| peppers, bell | 50 plants | 24 | 150 lb | 75 | |

| potatoes, Irish | 10 lb | 4 | 12 | 150 lb | 100 |

| potatoes, sweet | 75–100 | 12 | 100 lb | 120 | |

| pumpkins | ½ oz | 1–2 | 48 | 300 lb | 90–110 |

| radishes | 1 oz | ½ | 1 | 40 lb | 28 |

| rutabagas | ½ oz | ¼–½ | 12 | 90 lb | 90 |

| spinach | ½ oz | ½ | 4 | 70 lb | 45 |

| squash, summer | ½ oz | 1 | 36 | 150 lb | 55 |

| squash, winter | ½ oz | 1 | 48 | 100 lb | 90 |

| tomatoes | 35–65 plants | 18–36 | 125 lb | 70 | |

| turnips, greens | ¼ oz | ¼–½ | 2–3 | 50–100 lb | 50 |

| turnips, roots | ¼ oz | ¼–½ | 2–3 | 50–100 lb | 60 |

| watermelons | ½ oz | 1½ | 48–72 | 60 fruit | 85 |

Maintenance

Mulching

A mulch is any material used to cover the garden soil’s surface to protect plant roots from heat, cold, or drought, to keep fruit clean, or to control weeds. Mulches help to make more attractive, higher-yielding vegetable gardens.

Garden mulch changes the environment where the plants are growing, resulting in better plant growth and higher yields. When deciding to use a mulch, weigh the advantages against possible disadvantages, cost, and availability of a particular mulching material.

There are many types of mulching materials, but they can be divided into two general categories: natural and synthetic. Natural mulches are organic materials, such as straw, hay, compost, composted bark, paper, or pine needles. Synthetic mulches are plastics, rubber, and landscape glass.

Natural Mulches

Natural mulches consist of organic plant and/or animal residue or by-products. They are generally spread over the ground surface around established plants or over the entire growing area in a layer 2 to 5 inches deep. Composted sawdust, bark, wood shavings, leaves, grass clippings, rice hulls, ground corncobs, and composted animal manures may also be used. Pine needles, hay, and straw are light and airy, so a 4- to 5-inch-deep layer is needed for them to be effective.

Most natural mulches have some fertilizer value and are good soil conditioners when worked into the soil. They improve both the physical and chemical properties of soil. The organic matter incorporated into the soil improves water-holding capacity, nutrient availability, and soil aeration.

Some mulching materials, such as pine needles, peat, and oak leaves, are acidic and lower the soil pH once they are tilled into the soil. Soil testing and liming, as recommended, can counteract the acidification of soils.

Finely ground peat moss makes a poor mulch. It is easily blown around by wind and becomes almost water repellent when dry. Peat is best used to improve soil organic matter content, moisture-holding capacity, and structure by mixing it with the soil.

Organic mulches are summer mulches since most of their advantages are realized in hot weather. A summer mulch protects soil from compacting rains, foot traffic, drying winds, and heat. It also controls weeds by excluding light from germinating seeds and seedlings. Mulches prevent some weed problems, reducing competition for light, water, and nutrients.

By reducing soil moisture loss, mulches reduce the need to water, and garden vegetables suffer less in dry periods. Organic mulches also increase the water absorption rate of soils. The reduced soil temperatures under organic mulches encourage root growth in the upper soil layer where there is more oxygen and fertilizer.

Mulch also reduces soil erosion and keeps soil from splashing on vegetable leaves and fruit during rains or sprinkling. This can reduce losses to some diseases such as early blight.

Apply organic mulches to warm-season vegetables when the soil has warmed sufficiently for good plant growth and when plants are large enough that they won’t be covered. Keep the soil free from weeds until summer mulch can be applied. Mulching warm-season vegetables too early in the growing season makes them susceptible to frost injury by preventing soil warming and insulating plants from any warmth in the soil.

Organic mulches are beneficial when applied to cool-season vegetables like broccoli, cabbage, and English peas in midspring. They help prevent rapid soil warming and drying and extend the growing and harvest periods.

Some organic mulches require changes in garden fertilization methods. Sawdust, wood shavings, and ground corncobs are low in nitrogen. As they decompose, nitrogen is drawn from the soil, causing a nitrogen shortage in the mulched vegetables. To prevent this, add ¼ pound of 34-0-0 or its equivalent to each bushel of sawdust, shavings, or corncobs before applying. When it is time to side-dress, pull the mulch back from plants and apply fertilizer to the soil surface. With sawdust, compost, or bark, apply fertilizer to the mulch surface and water it in.

Always remember that dry mulch may catch fire.

Synthetic Mulches

Plastic mulches are springtime mulches. They help warm the soil (permitting early planting), promote rapid growth, allow early harvest, and control weeds.

Plastic mulches reduce soil moisture loss and protect fruits and leaves from soilborne diseases. Black plastic is the most used synthetic mulch. It is widely available, relatively inexpensive, and comes in various widths and lengths. Use 11/2-mil (0.0015 inch) thick plastic.

Use clear plastic mulch only when the soil has been fumigated to kill weed seeds. Clear plastic warms soil more rapidly than black plastic, but weed seeds germinate under clear plastic.

Warm-season vegetables like cucumbers, melons, squash, tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant grow better and produce more when grown on black plastic mulch than on bare soil. Transplants can be set through plastic mulch by cutting round holes with a sharpened bulb planter. Use the same tool to plant seeds of widely spaced vegetables like squash and melons.

While frequently used with warm-season vegetables, plastic mulch can be used with cool-season vegetables like cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower to promote early growth. Plastic mulch is not used with vegetables that are closely spaced in the rows.

Black plastic mulch can also be used with plastic row tunnels to further promote early growth and harvest.

Applying Plastic

Prepare the soil completely before applying a plastic mulch. Incorporate fertilizer and lime, remove weeds and debris, and break up large clods. Rake the soil to prepare a smooth, level surface. Make sure the soil contains a good supply of moisture before being covered.

Plastic that is 3 to 4 feet wide is best for covering a standard garden row. Select a time to apply plastic mulch when there is little or no wind. Bury one end of the plastic and unroll it down the row. Get the plastic as straight as possible and in contact with the soil surface. Then, bury all edges to keep wind from getting under it and causing tears.

If you have a small garden that is less than 4 feet wide, use large sheets of black plastic to cover the whole area rather than covering individual rows. Be careful when stepping on wet plastic, as it can be slippery.

Soils lose less moisture from evaporation with plastic mulches, so you won’t need to irrigate as often. In prolonged dry periods and with vegetables that are in the garden for a long time, supplemental water becomes necessary. Because plastic keeps rain and sprinklers from irrigating the crops, you will need to irrigate the plants using other methods, such as drip irrigation or hand watering into the holes around each plant. The easiest way to irrigate with plastic mulch is to install a drip irrigation system or lay soaker hoses on the surface of the rows before covering them with plastic.

Because plastic mulch protects soil from leaching rain, the soil needs less fertilizer. When additional fertilizer is required, apply it through the planting holes and upside-down “T” slits cut at intervals into the plastic.

Although plastic warms the soil in spring, it can have disadvantages in summer. Excess heat can build up under the plastic, and high soil temperatures can injure plant roots and reduce yields. Rather than remove the plastic and lose the advantage of weed control, cover the plastic with pine needles, hay, or similar organic mulches to provide shade where the crop foliage does not.

Another technique is spraying black plastic mulch with white latex paint after an early crop to reduce the buildup of excess heat under the mulch during the summer. This will make it useful for summer and fall vegetables. The light-colored surface reflects much of the heat, and the other benefits of the mulch remain. At the end of the season, remove the plastic because it will not decompose in the soil as organic mulches do.

Newspaper

Newspaper is an organic material, but as a manufactured product it may be thought of differently from other organic mulches. Newspaper makes a good mulch when you use a thickness of several sheets. Hold newspaper to the soil surface with soil, sticks, rocks, or coat hanger wires.

Some gardeners use a thin layer of pine needles to hold the newspaper down. Apply a newspaper mulch after plants are established. Like other organic mulches, newspaper decomposes rapidly and adds organic matter to the soil.

Watering

Vegetable gardens usually need about 1 inch of water (630 gallons per 1,000 square feet) per week during the growing season. Gardens in sandy soil may need as much as 2 inches of water per week in midsummer.

Mulches that slow soil surface evaporation can reduce the amount of water needed. Soaker hoses and drip or trickle irrigation systems wet only the soil in the root zone and can cut the amount of water needed in half.

Adequate soil moisture is important for seed germination, uniform growth, and productivity. The most critical periods for adequate moisture are during seed germination, early growth, flower and fruit development, and root enlargement of root crops, and immediately following transplanting.

Sprinklers

There are several choices of garden sprinklers, ranging from the simple garden hose with a spray nozzle to semi-automatic equipment. Many portable lawn sprinklers are adequate for the garden. Adjust the rate of water application so that it is not faster than it can enter the soil. Water applied too rapidly runs off, resulting in erosion or puddles and causing soil compaction.

Place the sprinkler where plants will not interfere with the pattern of application. This often means mounting the sprinkler above the tops of the plants where wind may affect the distribution pattern. Place small cans throughout the garden to measure the amount of water applied and show the overlap necessary to approach an even application of water.

Since overhead sprinklers wet plant leaves, water early enough in the day to allow time for leaves to dry before night. This helps keep leaf diseases from developing and spreading. Each watering should wet the top 3 to 5 inches of soil.

Drip Irrigation

Soaker or perforated plastic hoses are excellent for watering the garden. Place the hose with holes up along one side of the plants or underneath an organic or plastic mulch.

Drip irrigation systems are available online and through mail-order catalogs, magazine ads, and local distributors. These systems usually consist of a supply line that connects to a garden hose and delivery tubes that are placed next to the plants. A 150-mesh filter is recommended to prevent clogging small pores and emitters. The systems operate at low pressure and deliver small amounts of water very slowly through pores in the delivery tubes or emitters punched into the delivery tubes.

Correct use of a drip irrigation system should keep vegetable plants actively growing in dry periods yet cause no problem when rain occurs following irrigation. The system, when properly operated, keeps soil at the base of the plant (root zone area) moist. This may require operating the system for short periods three or four times a week during dry weather. Never allow the soil to dry completely. Drip irrigation, when used correctly, prevents drought stress but is not designed to correct drought stress like sprinkler irrigation, which wets all the soil.

Single drip lines will not adequately water wide-row or raised-bed gardens, but several spray heads are available that do a good job in these special types of gardens when fitted to the drip irrigation delivery tube.

Drip irrigation systems have many advantages:

- Reduces water use by half or more.

- Water is placed where it is needed: at the base of plants and not in walkways.

- Large gardens can be watered all at once.

- Harvesting, cultivating, spraying, and other garden chores can be done while watering.

- Keeps plant leaves dry.

The major disadvantage of a drip system is the initial cost.

Insect Identification and Control

The average home vegetable garden may contain more than a dozen different types of vegetable crops, and each of these crops may be attacked by several different species of insects. Being able to manage and control these insect pests is one of the keys to successful vegetable gardening.

Insect pests can damage vegetables in several different ways. Pests like tomato fruitworms, cowpea curculios, stink bugs, and pickleworms cause direct damage by feeding on the fruit. Pests like tobacco hornworms, which feed primarily on the leaves, or aphids, which suck sap from the plant, cause indirect damage. Even though the fruit is not damaged directly, the plant’s ability to produce fruit can be reduced if it loses enough leaf area or sap. Pests like thrips and bean leaf beetles also can cause damage by transmitting plant diseases. In addition to the direct damage they cause, pests like corn earworms and cowpea curculios also contaminate food.

Even though many different species of insect and mite pests can occur in home vegetable gardens, they do not usually all occur at one time, so you probably will not have to “spend the summer spraying bugs” to have a successful garden. Many methods besides insecticide sprays can manage insect populations and keep them from reaching levels where insecticide sprays are necessary. Many of these methods are passive, requiring relatively little effort from the gardener, and many are things that you will do anyway if you want to grow a vigorous, productive crop.

Sometimes insect pest populations will reach damaging levels and you will need to treat them with insecticides. Apply these treatments only to the crop (or crops) being attacked. Rarely will you need to apply a broadcast treatment of insecticide to every crop in the garden. In fact, doing so can be counter-productive, causing pest problems that you otherwise would not have had. This is because unneeded insecticide treatments can destroy beneficial insects, allowing the pests that they were keeping in check to increase in numbers.

However, there are situations when repeated insecticide treatments may be needed to adequately protect certain crops. This is especially true when you are trying to produce a crop when pest populations are especially high (because of the time of year or planting location).

For example, yellow squash are very likely to experience heavy infestations of squash bugs and squash vine borers when grown in midsummer to fall. When grown in the same location year after year, southern peas are likely to experience heavy infestations of cowpea curculios if you do not apply timely insecticide treatments. Fall tomatoes normally experience heavy infestations of stink bugs and tomato fruitworms. There are many other examples, and experienced gardeners quickly learn which pests are especially troublesome in their area and when to expect these pests.

Common Garden Insect Pests

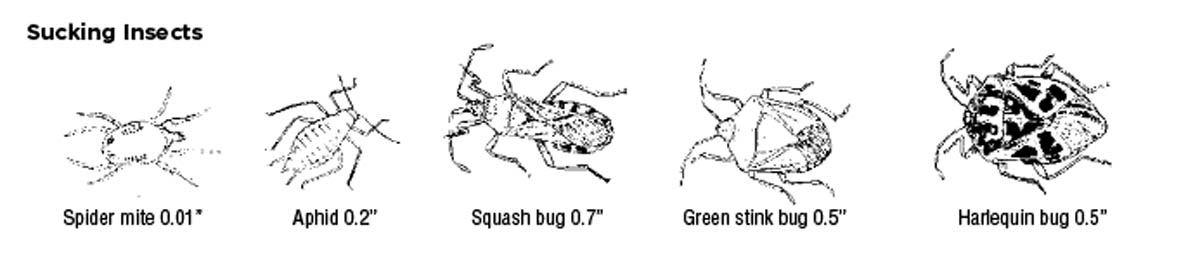

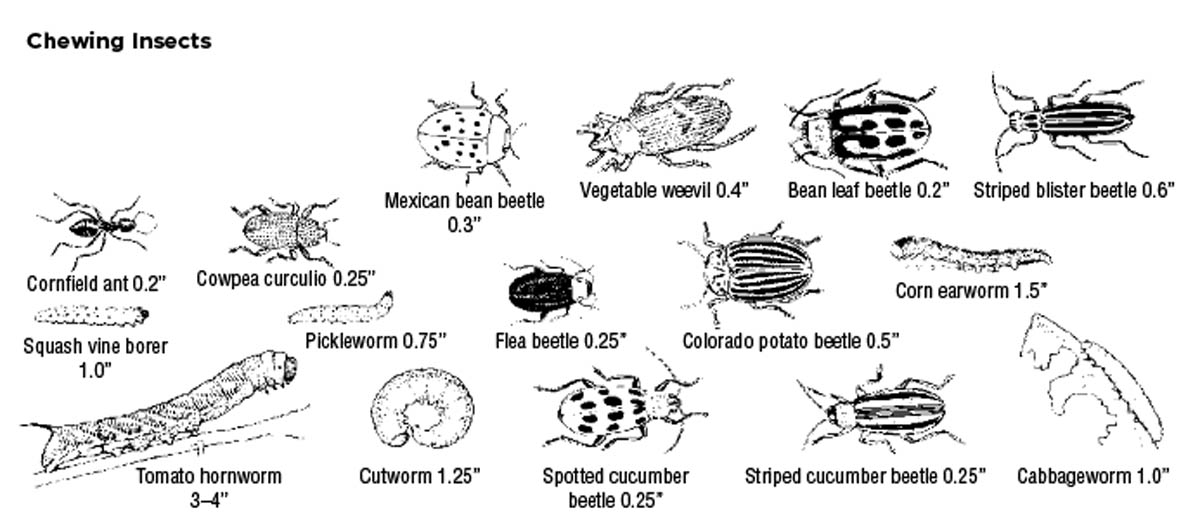

Insects damage plants by eating the foliage, boring in stems or roots, sucking plant juices, and attacking fruit. The type of damage caused by a particular insect depends on the type of mouthparts the insect has. Pest insects can be classified as having one of two different types of mouthparts: sucking or chewing.